The 'Lost Modernist': Michael O'Connell

-

Author

- Alison Hilton

-

Published Date

- April 18, 2016

<<<<Written by Adam Koszary, Project Officer.

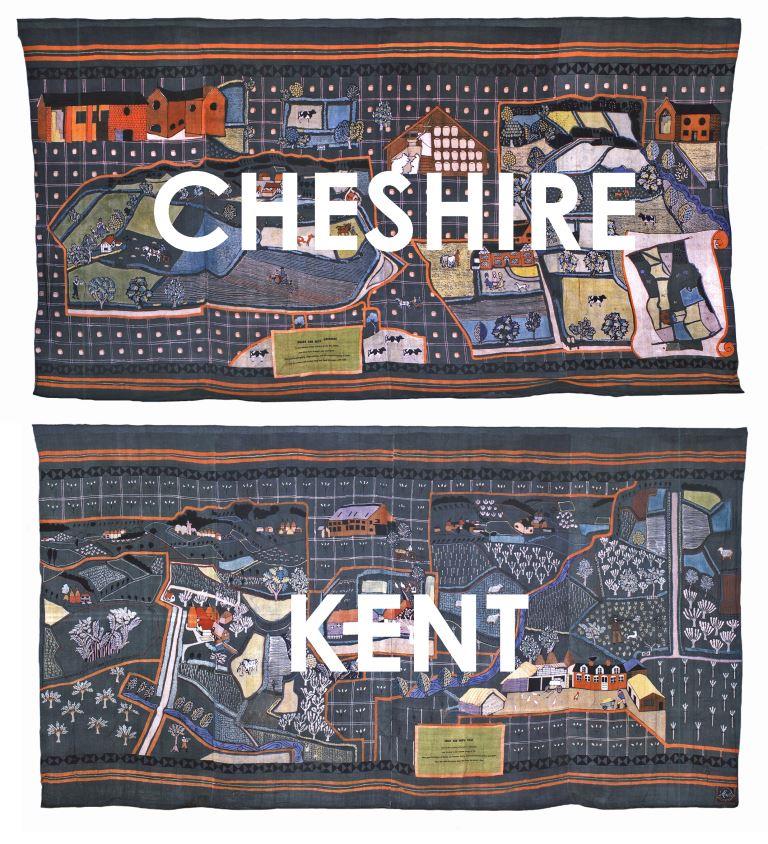

We’re asking you to help us decide which of our two wall hangings to display in the new Museum. Both were displayed at the 1951 Festival of Britain as part of a wider series exploring the British countryside, and have not been on public display for over 60 years.

They were designed and made by the artist Michael O’Connell (1898-1976). Described as the ‘Lost Modernist’, he was a textile artist whose style and colour typify the 1950s and 1960s. At the time he was considered stylishly bold, brash and modern, but his work is still relatively unknown.

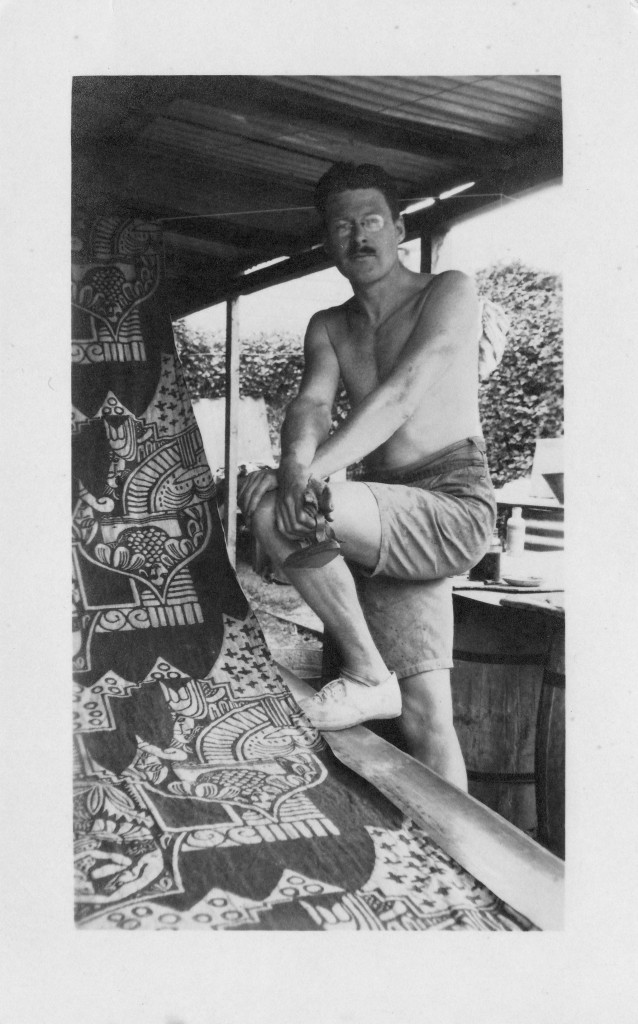

Artistically, O’Connell found his feet in Melbourne, Australia, where he honed his craft skills by building his own house in 1923, something he was forced into after his previous home (a tent) was condemned by a health inspector. His romantic lifestyle on the outskirts of Melbourne society, often journeying into the Australian bush to paint and draw, was a far cry from his upbringing in Dalton, Cumbria. His previous aim was to study Agriculture, but his artistic talents were never in question: when held as a prisoner of war in the First World War, one of his guards complimented his work and encouraged him to pursue a career in it.

It was also in Australia where O’Connell hit upon various pioneering methods of dying fabric with his wife, Ella Moody, both of whom were prominent in the Australian Arts & Craft Society. They returned to England in 1937 and developed a close working relationship with Heal’s of London, who proved instrumental after the Second World War in supplying fabric for the Festival of Britain wall hangings.

O’Connell’s commission required wall hangings to decorate the Country Pavilion at the Festival of Britain, held in May-September 1951. For the hangings themselves, O’Connell had to reflect the versatility and variety of farming in Great Britain, and so he took a tour of the nation, translating what he saw and experienced into his art. The result are seven hangings covering most of Great Britain, representing the distinctive character of our regions and providing an artistic snapshot of the state of British farming in the early 1950s.

After the Festival of Britain the popularity of Michael’s work increased and he received commissions to create murals for public buildings, restaurants, factory canteens and showrooms. His work was exhibited in New York, Melbourne and London. In the 1960s, he began to travel widely and to teach his techniques in art schools. He also worked with architects, producing murals for universities and churches.

In 1970, a devastating fire destroyed his workshop, most of his notebooks and records, and badly damaged his adjoining house. With the help of students and friends the property was rebuilt, but in the following years his eyesight began to fail. In 1976, he was found dead from self-inflicted gunshot wounds.

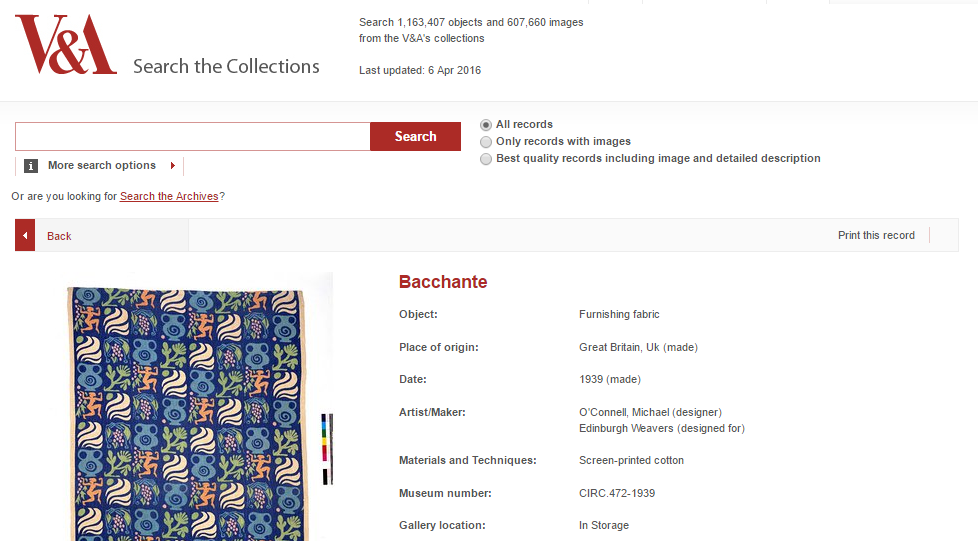

His work lives on in museum collections in Australia and the UK. While the MERL holds the Festival of Britain wall hangings, the V&A museum also has a large collection of his early work.

Have you voted on which wall hanging to display yet?

-

Tags