Folklore & Storytelling: MERL and the Pitt Rivers Museum

-

Author

- Alison Hilton

-

Published Date

- January 8, 2015

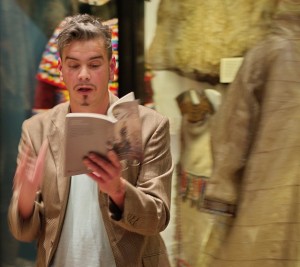

<Ollie Douglas, our Assistant Curator, gave a gallery talk at the Pitt Rivers Museum recently and naturally homed in on objects relating to rural life. Here’s what he found…

I recently had the enjoyable experience of giving a gallery talk at the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, on the subject of folklore and object collecting. This formed part of an ‘after hours’ event themed around folklore and storytelling. I did my best to steer a rather large number of visitors on a somewhat congested tour of some the Museum’s most intriguing items. This began beside a case of lighting equipment close to the entrance where I chose to describe how numerous late-nineteenth century folk collectors spoke of the demise of traditional technologies under the ‘glare’ of electric lighting, using such examples to underline the importance of recording old ways of life. I highlighted a few objects gathered by prominent folklorists and that I think resonate powerfully with MERL’s own holdings. These included an English horn lantern similar to an example held here and of a type used commonly by shepherds because of their soft light and hard-wearing panes.

I recently had the enjoyable experience of giving a gallery talk at the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, on the subject of folklore and object collecting. This formed part of an ‘after hours’ event themed around folklore and storytelling. I did my best to steer a rather large number of visitors on a somewhat congested tour of some the Museum’s most intriguing items. This began beside a case of lighting equipment close to the entrance where I chose to describe how numerous late-nineteenth century folk collectors spoke of the demise of traditional technologies under the ‘glare’ of electric lighting, using such examples to underline the importance of recording old ways of life. I highlighted a few objects gathered by prominent folklorists and that I think resonate powerfully with MERL’s own holdings. These included an English horn lantern similar to an example held here and of a type used commonly by shepherds because of their soft light and hard-wearing panes.

Further on I explored examples of hazel water-divining rods collected in rural Somerset by the prominent nineteenth-century thinker Edward Burnett Tylor (1932-1917). Tylor wrote about cultures from all over the world but often illustrated his arguments with examples taken from closer to home. Indeed, one explanation of his influential idea of ‘survivals’ (i.e. older ways of life seen to linger on in modern society) focussed on similarities between protective symbols seen on silver amulets from Italy and of shapes seen on decorative British horse brasses. Whether or not he was correct about this connection there are certainly many examples where amulets were used in England to protect animals from harm. One fear amongst stockmen was that an enemy might put the ‘evil eye’ on their dairy cattle and thereby turn the milk sour. This was a means of making sense of ailments that were not well understood at this time. Indeed, problems with milk stemmed more likely from mastitis than they did from witchcraft! Nevertheless, the emergence of modern veterinarian practice and greater scientific knowledge didn’t always stop our forebears from attempting to protect their animals in unusual ways. Further examples in the Pitt Rivers Museum (some collected by Tylor himself) show that when an animal died in unexplained circumstances, one common course of action was to cut out its heart, pierce it with nails, and stuff it up the chimney. As the heart blackened in the smoke of the fire, the person who wished harm on your herd would also suffer.

The evening itself offered a brilliant context in which to promote the work of both the Museum of English Rural Life and of The Folklore Society, with which I also have connections. Alongside music, storytelling, and the dulcet tones of my tour, the event showcased the ongoing collecting practices of the inimitable Doc Rowe and a reading from the University of Reading’s own Obby Robinson. Obby read from his most recent collection—”The Witch-House of Canewdon and Other Poems”—which drew inspiration from English folklore practices and featured in a lunchtime recital at MERL in March of last year. This has left me thinking about creativity, storytelling and folk beliefs and of how we might begin to examine traditional forms of animal protection into our new displays. Check up your chimneys – I’m on the lookout for a heart stuck with nails!